The Snowflake Principle

N

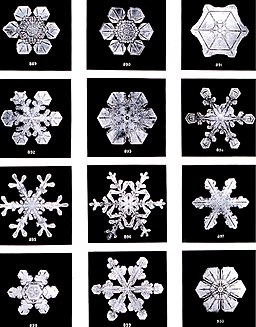

o two snowflakes are alike, we are told. People are like snowflakes, we are told. Unique. Special.

It’s true that snowflakes are technically unique. But if you’ve ever watched a heavy snowfall through a window on a winter’s night, in the comfort of a toasty warm room so you could watch for a long time, then it might’ve suddenly struck you that being told you are special like a snowflake should not make you feel very special at all. They aren’t that unique. And there are so very many of them.

How much snow falls in a single winter? We actually know the answer to that. A million billion cubic feet of snow falls on Earth each year, and each cubic foot contains roughly a billion snow crystals.[1] Now consider that snow has been falling on our planet for billions of years. What is a single snowflake to the history of snowing?

What is most remarkable about snowflakes is not their uniqueness but their sameness. They are unique in tiny ways, but their similarities outweigh their differences. The individual snowflake is insignificant. It has its brief life, blown about in the chaos of the snowfall, but soon crashes to the ground, and then either melts or is buried and lost forever.

The individual snowflake is indeed a wonder of nature, no less wonderful for the fact it comes from a big family. But it cannot be called “special,” unless by that word you mean something that can apply at once to every other snowflake that exists, has ever existed, or will ever exist.

Perhaps the theory that people are like snowflakes is correct after all. We are wonders of nature, but no one of us is special unless so are we all.

The biologist and blogger PZ Myers (his blog Pharyngula is a must read) describes a similar idea called the mediocrity principle:

The mediocrity principle simply states that you aren’t special. The universe does not revolve around you, this planet isn’t privileged in any unique way, your country is not the perfect product of divine destiny, your existence isn’t the product of directed, intentional fate, and that tuna sandwich you had for lunch was not plotting to give you indigestion. Most of what happens in the world is just a consequence of natural, universal laws — laws that apply everywhere and to everything, with no special exemptions or amplifications for your benefit — given variety by the input of chance.[2]

For those who’ve been told since childhood by adoring relatives that they are special, this revelation is unpleasant at first. We’ve been propped up on pedestals and have no interest in stepping down. It feels good to be cherished.

But when adults use the word “special” to praise children, what they most often really mean is “better,” and there is something vile in raising a child to believe she is better than other children. This sort of praise fosters a destructive competitiveness in children, and sets them up for sibling rivalry and approval addiction, which later in life will bring them nothing but dissatisfaction and disappointment. We teach kids to delude themselves that they are globally better or worse than their peers, when in truth such comparisons are meaningless. We teach them to seek their sense of worth through external achievements. In other words, we teach them to be unhappy adults (like us).

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2012 William Bloom

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2012 William Bloom